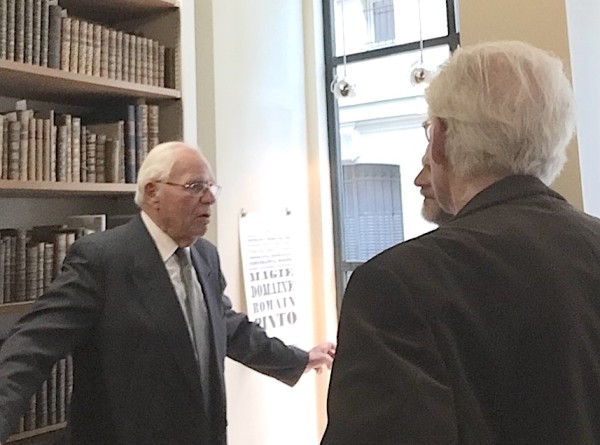

André Jammes receiving two American collectors, May 2015.

News came that André Jammes had passed away at the age of ninety‑eight and a half. To those who worked with him, he remains above all a master of method, a man who taught material bibliography less through speeches than through his writings, less through words than through silence, patience, and high standards.

His teaching came with a simple and ruthless, rule: no interruptions, no questions. Whenever I dared to ask "What is it? Who made it? What does it represent?", he would turn back to his work and his silence, sometimes for weeks. By contrast, when he placed a mysterious photograph on the table, he encouraged me to list the clues, to venture hypotheses. The same method is now applied with my students: they are free to ask any question, but only in order to submit hypotheses, comparisons, lines of reasoning.

My itinerant bookselling activity began in 1989. In 1991, a first visit was made to the Jammes bookshop in Saint‑Germain‑des‑Prés, together with a young colleague, who was starting out at the same time. We wanted to propose a recent acquisition, a copy of Conrad Gessner's Bibliotheca Universalis, one of the very first works with a universal bibliographical ambition, printed in Zurich in 1545, a good copy that Jammes judged "very fine" and purchased without a second thought, before letting the two young booksellers leave the small shop in rue Gozlin.

On the doorstep I turned back and, summoning my courage, told him that I had been on my own for only two years, but that I had been working markets since the age of thirteen, and that I hoped to join the antiquarian booksellers' association. "Would you agree to be my sponsor?" He smiled, hesitated for a moment--my young colleague seemed slightly annoyed by my boldness--and then André gave that "yes" which made him my mentor for the years that followed.

On returning from a trip, especially from countries he had never been able to visit, Jammes always asked to be informed. He would appear in turn, calm, attentive, ready to listen. Rucksacks and suitcases were emptied, books laid out one by one on the table: a volume found in Damascus, printed in Alexandria during Bonaparte's French occupation, bought in a bookshop where the young employees walked barefoot; or a book from Moscow, published in the early years of the Revolution, its hand‑colored plates showing traditional Dimkovo toys, intended to help several families through the particularly harsh winter of 1917. He listened to everything without interrupting: the story of the journey, the poverty of the shops, the tales of the booksellers, the price paid. Then he would take each volume, place it gently on a growing pile in front of him, and simply say: "Very good. And what else?"

In those early years, at each visit, André Jammes would give me one of his catalogues. Sometimes they were copies more than thirty years old, which had lost nothing of their relevance. These catalogues had been pioneering in their fields and never went 'out of date': the fruit of stubborn patience, meticulous research, endless checking--lmost monastic work. A Benedictine monk in fact helped him review and verify all his bibliographical notes. Among the most notable are the catalogue on "libertins érudits" (erudite libertines), the one on Enlightenment philosophers, and various catalogues devoted to writing models. Nearly 50 years later, almost all of them still serve as reference works and continue to be used in American universities. Through them, one learns as much about the history of books, as about the art of describing them.

Over time, Jammes began to offer a more advanced kind of teaching: remarks of inestimable value on physical bibliography, on the analysis of paper, typefaces, bindings, and on the history of the book trade. He spoke of the customs of the antiquarian book world, and of the ways in which certain obstacles had been overcome collectively. One example will suffice. The 1929 crash did not fully hit France until four or five years later, but then with terrible force. Soon, throughout Paris, there was only one person left who could still buy rare books. There was only one bookseller whose door this client would open, and all the others, wisely, agreed to work through him in order to keep a minimum of cash flow and continue working during that difficult year. That sole client in 1934 was the president of the bankruptcy court at the Paris commercial court.

Together with his wife, Marie‑Thérèse, Jammes privately explored two areas that the Paul Jammes bookshop did not officially handle--two different fields of the image. On the one hand, the history of popular imagery, from messenger boxes and 16th‑century broadsides to the hand‑colored prints that decorated rural houses across many parts of Europe and Russia.

On the other, the history of photography. This second field had been suggested to him when he was still only the young son of a bookseller. Around 1949, during a dinner of the Association du Vieux Papier, after a lecture on the earliest books illustrated with photographs, the speaker suddenly turned to André, the youngest person at the table--he was only 22 st the time--and said: "Perhaps you are the one I should be talking to. You are the youngest; this field is particularly promising, but particularly difficult. It will demand endless patience, perseverance, scholarly research, and absolute scientific honesty." Years later, the exact trace of that dinner and that sentence was located, at the very point where photography began its path into major museums.

Jammes liked to say, smiling, that he and Marie‑Thérèse had probably spent more money, time, and energy on popular imagery than on early photography. This first passion--broadsides, colored prints, images from European and Russian rural traditions--has remained a field almost entirely in the shadows, the object of minimal research. The second, the collection of early photographs, became by the end of the 20th century a global craze, profoundly transforming both the market and the historiography of photography--and this, in part, thanks to them.

The first Jammes sale and a training as expert

When André and Marie‑Thérèse prepared the first major sale of part of their photography collection at Sotheby's in London, in October 1999, they selected the finest prints, those that would make history on the market. But there remained a whole group of neglected photographs: prints that were sometimes imperfect or torn, by anonymous authors, with sitters and places that no one had yet been able to identify. It was on these images--the "rejects", in a sense--that Jammes decided to build a real training ground, so that another expert in photography might emerge. He summoned me, pointed to an initial pile of these "non‑selected" photographs, and told me to take them away, without asking a single question, of course. What he did encourage me to do was to come back and submit my hypotheses and the first results of my research, on one condition: that I follow his Benedictine method, going to libraries, digging into older publications, multiplying cross‑checks.

From his exacting standards and from his silences, he forged a tool for transmission. Through these photographs to be identified, analyzed, and described, his way of working was in fact passed on. Each subsequent session could give rise to impromptu stories, gradually revealing how archives travel through long periods of indifference.

This can be illustrated with an example drawn from notes taken during one of our conversations, on Saturday, 24 March 2012. The topic was Joseph Nicéphore Niépce (1765–1833), and in particular one very specific issue: the portrait attributed to Niépce, drawn by Laguiche, which still illustrates several encyclopedic articles devoted to him.

André recalled that this drawing, signed by Laguiche and dated 1795, has with Niépce only a purely geographical connection. It was found in Chalon‑sur‑Saône by a dishonest dealer‑collector, as an unidentified portrait. The name "Niépce", added on the reverse, had no other purpose than to increase its value.

The dealer then had the skill to convince Lécuyer, who was preparing his Histoire de la photographie, to accept it as a portrait of Niépce and to reproduce it as a full‑page plate. He then sold it at a good price to a local collector. Some time later, the drawing passed into the hands of a bookseller who knew that the attribution was false, but nevertheless catalogued it as Niépce, citing Lécuyer's authority as his only argument. Today that portrait is in Austin, Texas, alongside the famous View from the Window at Le Gras.

André added that he later discovered the intimate and tragic reason behind the dealer's repeated dishonesty: a son who was mentally ill – dangerously so – whom he wanted to keep out of the asylums, and whom he kept, shamefully, locked up in his small Paris apartment. He needed urgent money to hide him without any institutional medical care.

Perhaps it is thanks to André and Marie‑Thérèse that the history of photography, even if it can still appear confusing, remains a field in which rigor and patience are expected, where speculators sometimes encounter quiet resistance, and which will continue to offer future generations of students material for patient research, rewarded by many discoveries yet to come.

Share This