Changes and Challenges at Rencontres d'Arles Photography Festival

Oscar Rejlander Album Sells for over $130,000 in England

Phillips Opens New Auction Facilities in London

Griffin Museum of Photography Selects Focus Award Winners

Photo Book and Catalogue Reviews: In Ansel Adams' Footsteps, Kertesz's Raison d'Etre, and more

Penelope Niven, Noted Steichen Biographer, Dies

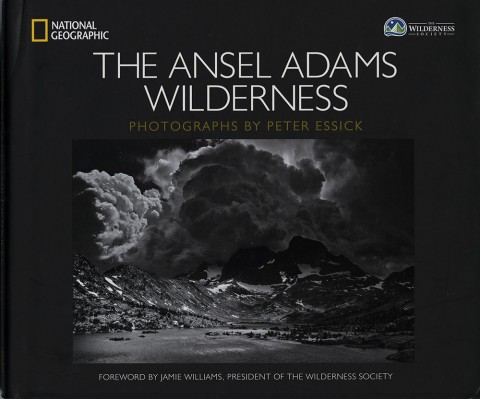

THE ANSEL ADAMS WILDERNESS.

Photographs by Peter Essick. National Geographic Books/The Wilderness Society. 108 pp., approximately 50 black-and-white plates. ISBN No. 978-1-4262-1329-8; hardbound, US$22.95. Information: http://www.nationalgeographic.com/books.

Few nature photographers have attained the stature of Peter Essick, after nearly three decades as a frequent contributor to National Geographic magazine and a great deal of photojournalism that has left its mark on the environmental movement. As a result, he's more than entitled to make an ambitious tribute to Ansel Adams with this new book. It features stunning images taken in the area of California's High Sierra, between Yosemite National Park and Mammoth Lakes, that was renamed the Ansel Adams Wilderness following the great man's death in 1984.

Essick's project is a worthy update of Adams' artistry for at least two reasons. The first is that he doesn't make the trite mistake of attempting to recreate any of the famed Adams images. Instead, he sought out fresh but complementary terrain in the grand style of the master. The second reason is more technical; as he notes in the book's extensive Photographer's Notes section, he chose not to duplicate Adams' choice of equipment--a four-by-five view camera and black-and-white film--opting instead for digital images made with a Canon EOS Mark III and Mark IV through a range of lenses and with exposure times from as long as four seconds at F/22 to 1/3000 of a second at F/8. "Adams was a great believer in using the latest technology," Essick writes, certain that if Adams were alive today he would choose similar, if not the same, photographic tools.

It's hard to argue with that logic and with the ease of use afforded by today's high-end digital cameras. Purists can argue that this technological advancement makes it altogether too easy to capture the sort of majestic images Adams had to work so much harder to create, and they might have a point. It's clear that photography is being altered by the ubiquity and high quality of even smartphone photos, which allow almost anyone to take pictures of greater clarity and complexity than they could have hoped to do in a previous era.

Yet Essick's work in the footsteps of Adams is clearly that of an uber-professional in his prime. From the long-exposure microcosm of a frosted Aspen leaf to the macro bird's-eye view of pines in snow (taken from a Cessna 180), Essick proves that the Adams Wilderness is an infinity of visual wonder, requiring an artist's fine eye and deeply knowledgeable camerawork to do it justice. Thus, the careful blend of tones and compositional mastery of his new photos of Thousand Island Lake, or of wind-whipped whitecaps against the mountain basin of Dana Lake are spectacular artifacts. And when Essick turns to Adams' touchstone subjects, with a shot of a huge waning moon setting over the granite cliffs near Donahue Pass, he makes something startlingly new, combining an earthly moonscape with its lunar equivalent.

This book is full of such revelations, and makes the most of the Canon's sensitivity to low light (which Adams would have delighted in) to capture difficult (and astonishingly delicate) images of the Milky Way as well as the moody sunset studies and the snow, wind, and waterfall lyricism Adams pioneered.

ANDRÉ KERTÉSZ: RAISON D'ÊTRE--PHOTOGRAPHS FROM THE CONCERNED PHOTOGRAPHER EXHIBITIONS, 1967-69.

Catalogue from the 2014 exhibition of the same name published by the Stephen Daiter Gallery, Chicago. Essay by Robert Gurbo. 104 pgs; approx. 50 plates. Information: info@stephendaitergallery.com; http://www.stephendaitergallery.com; phone: +1-312-787-3350.

Several of these superb images by the great Hungarian-born photographer André Kertész were seen at the last New York's AIPAD exhibition (including an intriguingly retouched version of the famous 1928 "Satiric Dancer," her limbs angularly sprawled on a Paris sofa), but all of them were part of the 1967-69 Concerned Photographer exhibitions that helped solidify Kertész's fame in the United States, after John Szarkowski put Kertész firmly on the map with a 1964 one-man show at the Museum of Modern Art.

As Robert Gurbo, Kertész estate curator, notes in this finely produced catalogue, Kertész was 68 and already retired when those displays began to affirm his status as one of the medium's master modernists, and only after he had failed to get any fashion work or gain more than spotty success in America during the 1930s. "The problem," writes Gurbo, "was that the subtlety and quietude which defined Kertész's work and which had drawn acclaim in Paris now resulted in questioning glances and withdrawn offers in a publishing industry more suited to high impact imagery. Earlier Kertész was warned by one LIFE editor that he talked too much with his pictures."

Such criticism suggests the philistinism of America's photography elite at the time, and is almost infuriating when one regards the classic images in this catalogue. The minimalism of the famous 1928 shot of a fork resting on the side of a plate arguably influenced a generation of art photographers, while the many street images of Paris in the '20s -- with their compassionate views of beggars, the infirm, of well-dressed Sunday strollers at Versailles, crowded cafes and tree-shadowed parks, or the cylindrical chimneys of rooftops, with an almost ghostly view of a distant Sacré Coeur above the roofline -- are paragons of compositional economy and unforced visual language. Rather than say too much, Kertész let the moment speak singularly for itself. Indeed, there's nothing forced or remotely posed about these photos (whether some were or not).

Of course, the early work, shot in his native Hungary in the World War I years, is what forged Kertész's vision. Turkish troops massed on boats, sharing space with their horses, or an indolent soldier slumped against a broken-down wagon in Romania, are detailed and beautifully exposed, early masterworks of verité, while the image of a blind Hungarian musician, being led by a child while he saws at his violin along the unpaved road of Abony, is a portrait of impoverished dignity.

While the images in this catalogue make the case for Kertész well enough, Gurbo's knowing essay provides in-depth historical context. It chronicles how Cornell Capa, brother of the great war photographer Robert Capa, a close friend of Kertész's, mounted the Concerned Photographers exhibitions in New York, proclaiming the artistic importance of photojournalism and founding the International Center of Photography in his brother's memory. He also made sure that Kertész would not be forgotten.

RIJKSMUSEUM STUDIES IN PHOTOGRAPHY: BETWEEN AD AND ALLEGORY: MARKETING PORTRAITS OF GERARD REVE (VOL. 12), AND COLOUR IN THE HOME: AUTOCHROMES BY JACOB OLIE JR. (VOL. 13).

Edited by Mattie Boom and Hans Rooseboom. Each volume approximately 50 pgs., with four-color photos. Limited editions of 750 copies each; hardbound; €22.95 each. Information: http://www.rijksmuseum.nl.

These latest in the Rijksmuseum series of photography monographs (funded by the Manfred and Hanna Heiting Fund) continue to make fine use of the Dutch museum's extensive holdings of more than 140,000 photographs from all centuries of the medium. The series brings scholarly analysis and compelling graphic illustrations to subjects that go unexamined in the Americas and much of Europe, and Volume 12, "Between Ad and Allegory," is a fine example. It explores the controversial Dutch writer Gerard Reve (1923-2006), whose homosexuality, conversion to Catholicism, and Oscar Wild-ean blasphemies made for a fair amount of scandal in the 1960s.

Outspoken and vain, Reve was happy to pose for a multitude of photos that helped him further his personal brand and market his collections of semi-autobiographical letters. As the Netherlands' first openly gay Catholic celebrity, Reve conflated erotic love and religion in his book "Nader tot U" (Nearer to Thee) of 1966, leading to his notorious "donkey trial" for heresy.

Monograph author Hinda Haest chronicles all of this with impeccable research and insight, while the numerous reproductions reveal Reve to us as a truly Wild-ean presence, taking full advantage of the camera's ability to nurture celebrity image. There are countless shots of the handsome Reve in his study, surrounded by myriad symbolic objects, at times with quill pen or wineglass in hand, staring defiantly at the lens, or posing Hamlet-like, in a Nehru jacket and with a human skull atop a nearby book. These are fascinating studies in sheer personality, at a time when Andy Warhol and the youth revolutions of the 1960s were in full swing, and iconoclasts like Gerard Reve were reshaping the culture debate just outside the Western mainstream.

As for Volume 13 of the Rijskmuseum series, it treads more traditional photographic ground, as author Laura Roscam Abbing explores the domestic autochrome photography of the Dutch chemist Jacob Olie, Jr. (1879-1955), 262 of which are held by the museum. Made between 1909 and 1932, Olie's photos are something of a tribute to his well-known photographer father, famed for his urban views of 19th-century Amsterdam. Olie junior was an amateur photographer but a committed chemist interested in the origin and perception of colors.

The autochrome process was a perfect medium for his experimentation. Developed in 1907 by the Lumiére brothers themselves, an autochrome is a color transparency, a glass plate with a light-sensitive coating and screen of starch grains dyed violet, orange, and green, The result is a coherent color image when held against the light or projected.

Olie's authochromes possess a wonderful immediacy, capturing the natural light and subdued natural colors of Dutch life, especially in such outdoor images as "The Kes Family in Volendamn", a 1923 autochrome which shows a family of six posed next to a Dutch canal. Mother and the squirming infant in her arms are somewhat blurred, which only adds to the appeal and liveliness of the image, while the white Dutch caps and long skirts are perfectly iconic. Other photos convey a similar charm and, often, a slight blur as well, but the details and, always, the pastel colorations and fidelity of the autochrome process are well represented, even though the Rijksmuseum series is printed on matte paper and might benefit from glossy illustrations that would conquer the graininess.

Still, Olie's images of these bourgeois families are of great interest, given their quantity and quality, while his lack of professional skill (some photos are over-shadowed, others simply too dark to do real justice to the sitters) is good for comparative study, especially when viewed in the context of the book's examples of professional autochrome work. These include Bernard Eiler's portrait of his wife, a stunning rhapsody in ivory and orange, or Sebastian Alphonse Van Beston's portrait, also of his wife, which is a superb mélange--of light streaming through a curtained window, flowers and fabrics, and golden blonde hair.

IN BRIEF: Several volumes from Stanko Abadzic, the prolific, Zagreb-based artist, are worth noting, as always. Abadzic is described more accurately, perhaps, in one of these books as a photographer/geographer (and "scenographer of his own cultural geography"), but what matters most is the consistent quality and curiosity he brings to any project. Thus, "ADRIATIC ROUTES" is his austere exploration of the spaces and light of the villages and sun-struck vacation spots along the Adriatic Sea, with people, often glimpsed from afar, as the inflection points in his angled studies of walls, sky, primitive architecture and raking sun.

Then there's "PARIZ – SKETCHES FOR A PORTRAIT OF THE CITY," in which Abadzic works on a larger and more complex geographic stage, seeking out the idiosyncratic perspectives we don't typically associate with Paris street photography (bicycle tracks in light snow beneath a lengthy overpass, for example) as well as his penchant for solitary figures in open, enigmatic spaces, or people diminished by postmodern structures, barriers and urban sterility.

There's also "SAMI U TOJ SUMI," Abadzic's collaboration with Czech poet Drago Glamuzina, for which Abadzic explores what may be his favorite geography, that of the female nude. These erotic black-and-whites are uniformly artful, studies in pure form and feminine beauty that combine all of Abadzic's interest in light, shadow, space, and abstraction. For more information about these books and Abadzic, visit http://www.contemporaryworks.net/artists/artist_books.php/1/4783/0, or phone 1-215-822-5662, or email info@contemporaryworks.net.

Brian H. Peterson was the former chief curator at the James A. Michener Art Museum in Bucks County, PA, and also a prolific arts scholar and photographer. Among his most recent publications are "THE SMILE AT THE HEART OF THINGS," a group of essays and personal reflections on the creative life, illustrated with some of his own and others' photography and artwork. Peterson pays tribute to the things that matter deeply to him, whether the sheer beauty of the natural world or the craggy handsomeness of his father's visage.

Peterson's other current volume, "THE BLOSSOMING OF THE WORLD" is a showcase for some of his most evocative photos (in addition to his essays on faith, science, and creativity) and reveal his versatility in creating rich, often abstracted images that range from cosmic earth-and-sky visions to absorbing close-ups of trees, stones, water, and light. Information: http://www.tellmepress.com, or contact his gallery at 1-610-997-5453; santa@santafineart.com.

Returning to the female nude, a recent exhibition of "Sabatier" prints by Todd Walker (1917-1998) at the Etherton Gallery in Tucson, AZ, are collected in a worthwhile catalogue that showcases the 1862 darkroom technique named for Armando Sabatier, who produced tone reversals by partially developing a print, briefly exposing it to light, then continuing the normal process. These gelatin silver images by Walker were shot in 1968-70, and their erotic emphasis on full-figured nudes is offset by the strangeness and liquid rhythm of the Sabatier effect. Information: 1-520-624-7370; info@ethertongallery.com; http://www.ethertongallery.com.

Then there is MICHAEL SNOW: PHOTO-CENTRIC, a catalogue from the Philadelphia Museum of Art's recent exhibition on the venerable Canadian filmmaker, an artist who is widely regarded as a pioneer of conceptualism and multimedia. From his seminal 1967 film, "Wavelength," which explored the experience of time and space in what he described as a "45-minute zoom", to his many photographic works, Snow has been a groundbreaker. This exhibit explored Snow's postmodern interest in self-reflexive materials and subjects, and his broad photographic experimentation in general. Helpful essays by Adelina Vlas and Snow himself are included. Information: http://www.philamuseum.org.

In a complement to Snow, among the many emerging photographers who have fresh perspectives, Ross Winter is a Toronto-based artist whose "THROUGH A GLASS DARKLY" reflects his Cubist take on urban surfaces, with well-conceived images of massive buildings and their mirrored and glassed architectural skins. These two-dimensional objects fragment our viewpoint and bring dense visual dimension to the modern experience, at least through Winter's lens. Information: http://www.rosswinter.me, or email s.rosswinter@gmail.com.

Matt Damsker is an author and critic, who has written about photography and the arts for the Los Angeles Times, Hartford Courant, Philadelphia Bulletin, Rolling Stone magazine and other publications. His book, "Rock Voices", was published in 1981 by St. Martin's Press. His essay in the book, "Marcus Doyle: Night Vision" was published in the fall of 2005. He currently reviews books for U.S.A. Today.

(Book publishers, authors and photography galleries/dealers may send review copies to us at: I Photo Central, 258 Inverness Circle, Chalfont, PA 18914. We do not guarantee that we will review all books or catalogues that we receive. Books must be aimed at photography collecting, not how-to books for photographers.)

Changes and Challenges at Rencontres d'Arles Photography Festival

Oscar Rejlander Album Sells for over $130,000 in England

Phillips Opens New Auction Facilities in London

Griffin Museum of Photography Selects Focus Award Winners

Photo Book and Catalogue Reviews: In Ansel Adams' Footsteps, Kertesz's Raison d'Etre, and more

Penelope Niven, Noted Steichen Biographer, Dies

Share This