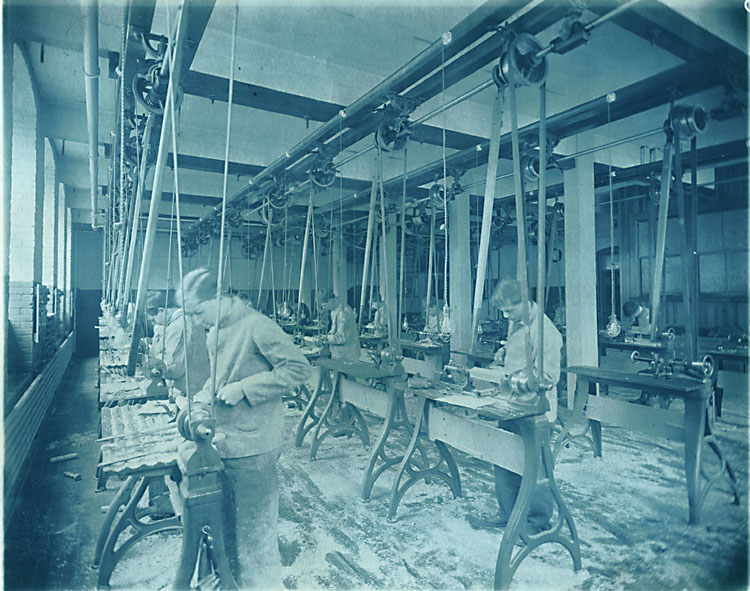

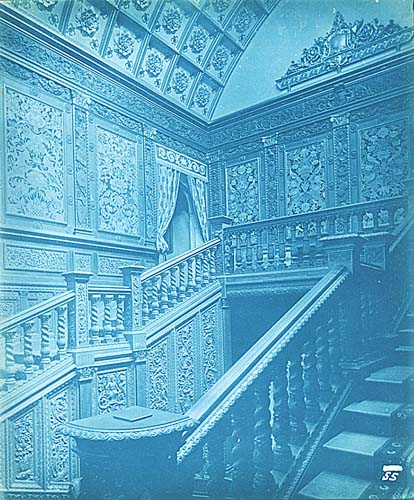

Albert Levy (attributed to) - Paris Exposition of 1900

The cyanotype process was invented and named by Sir John Herschel in 1842, but was most popular around the turn of the century when it was adopted by a large number of amateur photographers. These photographers found that the process was easy and inexpensive to use.

Although typically used by weekend amateur photographers, a number of studios and more important photographers utilized the process, including Henry P. Bosse, the influential Arthur Wesley Dow, Henri Le Sec, Georges Poulet (See: Blau, Aurora Argentina: George Poulet, Cyanotypes 1890-1894) and Mederic Mieusement. It is not surprising to find that the architect and photographer Albert Levy utilized the process. Many contemporary photographers also make use of this "alternative" process, including John Dugdale and Gerard Niermont.

Paper is simply sensitized with ferric ammonium citrate (citrate iron and ammonia) and potassium ferricyanide. Light exposure changes part of the ferric salt to the ferrous state (and a portion of the ferricyanide to ferrocyanide, creating a pale blue image consisting of ferrous ferrocyanide. After exposure, the cyanotype is washed in water. Washing removes any soluble, unreduced salts, leaving behind the insoluble ferrous ferrocyanide. After drying, the ferrous ferrocyanide slowly oxidizes to a deeper blue tone. No enlarger is necessary and many photographers simply exposed prepared cyanotype paper in a contact frame to the sun and then processed the results.

Henry P. Bosse -- Lucia

The usually brilliant blue images typically have a matte surface, because they were commonly made on simple writing paper, but some period photography darkroom information sources suggested that "hard, calendared, or richly sized papers give greater contrast and that soft papers, even with surface sizing (unless Baryta coated), give softer prints and finer gradations." Prints were even made on cloth.

Because iron salts are used (rather than silver compounds) for the light-sensitive material, cyanotypes are highly stable. Architectural blueprints were made by the same process.

There were a number of special toning processes that could turn such prints black, sepia, etc., but they were not recommended. As Sigismund Blumann's widely used "Photographic Workroom Handbook" noted, "Our most careful and persistent experiments, and the search of years for a truly satisfactory way of accomplishing the feat have resulted in partial success, at best. We therefore advise that if the reader desires prints in colors, he use other processes. A Blue Print is beautiful as such."

One of the best publications on the subject is Mike Ware's "Cyanotype: The History, Science and Art of Photographic Printing in Prussian Blue", which was published by the British Science Museum and the National Museum of Photography, Film & Television.

Ware's research on the cyanotype suggests several conservation issues with cyanotypes, including the following:

--They were faded by visible light, but this reaction was substantially reversible if the cyanotype was moved to dark storage. Cyanotypes may be safely exhibited at up to 50 lux illumination.

--Prussian blue was rapidly and irreversibly hydrolyzed to ferrocyanide and hydrated ferric oxide (sensitivity to bleaching by alkali can be greatly diminished by treatment with nickel (II) salts).

--Significant amounts of image substance were irreversibly lost from cyanotypes in aqueous washing.

Exhibited and Sold By

Contemporary Works / Vintage Works, Ltd.

258 Inverness Circle

Chalfont, Pennsylvania 18914 USA

Contact Alex Novak and Marthe Smith

Email info@vintageworks.net

Phone +1-215-518-6962

Call for an Appointment

Share This